Sounds can knock drones out of the sky

Knocking a drone out of the sky is sometimes possible using an invisible weapon -- sound.

The vulnerability in drones comes from a natural property of all objects -- resonance. Take a wine glass: if a sound is created that matches the natural resonant frequency of the glass, the resulting effects could cause it to shatter.

The vulnerability in drones comes from a natural property of all objects -- resonance. Take a wine glass: if a sound is created that matches the natural resonant frequency of the glass, the resulting effects could cause it to shatter.

The same principle applies to components inside drones. Security researchers at the Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (KAIST) in Daejon, South Korea, analyzed the effects of resonance on a crucial component of a drone, its gyroscope. Their paper will be presented next week at the 24th USENIX Security Symposium in Washington, D.C. A gyroscope keeps a drone balanced, providing information on its tilt, orientation and rotation, allowing for micro-adjustments that keep it aloft. Hobbyist and some commercial drones use inexpensive gyroscopes that are designed as integrated circuit packages.

In some cases, the gyroscopes have been designed to have resonant frequencies that are above the audible spectrum, said Yongdae Kim, a professor in KAIST's electrical engineering department. But others are still in the audible spectrum, making them vulnerable to interference from intentional sound noise. Matching the resonant frequency of a gyroscope causes it to generate erroneous outputs, which have an effect on its flight, Kim said.

Kim's team studied 15 types of gyroscopes from four vendors. Most came from two companies, STMicroelectronics and InvenSense, whose gyroscopes are used in a variety of drones. Seven of the gyroscopes resonated at their own resonant frequencies when encountering a matching sound. At the resonant frequency, the gyroscopes "spit out very strange outputs," Kim said.

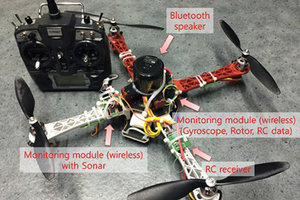

To compensate for this, many gyroscopes are designed so their resonant frequencies are higher than the audible range. For example, many mouses used for gaming are designed to avoid the matching of resonant frequencies to avoid game disruptions, Kim said. It is possible, however, to affect some kinds of drones using sound. For their tests, the researchers attached to a drone a small, consumer-grade speaker that was wirelessly connected to a nearby laptop.

The drone takes off normally, but when the right noise is played through the speaker, it smacks into the ground. "When the gyroscope starts fluctuating, it affects the rotor speed directly," Kim said. At 140 decibels, it would be possible to affect a vulnerable drone up from around 40 meters away, Kim said. For a real attack, it's not going to be possible to attack a drone by attaching a speaker to it. But Kim's team did experiment a bit with more realistic attack scenarios, analyzing the distance that would be needed from a drone to a sound source.

The main problem is aiming and tracking. "We are not Lockheed Martin or Northrop Grumman," Kim said. "We cannot make those weapons in our lab." Still, they tried some small-scale efforts. In one experiment, Kim's team embedded an audio module into a police shield. The problem with the shield is that it is difficult to continually track a drone in order to disrupt it. Even if the attack is initially successful, the drone starts to move so erratically that it become hard to track.

"Directionality matters a lot," he said. "It was pretty difficult." In another attempt, they built a kind of sonic wall, comprised of an archway containing speakers. The problem with the archway is that the drone passes too quickly through the ideal attack zone. But there are a variety of sound-related offensive and defensive devices already on the market. For example, the LRAD Corporation makes the 450XL, which it terms an "acoustic hailing device." It can be mounted on a vehicle or a tripod and can project a voice message up to 1,700 meters.

Japanese fisherman have used sound devices against environmentalists trying to disrupt their whaling operations, focusing intense, loud sounds against pursuers. Combined with a tracking radar, those type of devices could make such attacks on drones more viable. So how to defend against a sound attack? The key is insulating the gyroscopes from interference, using shielding or foam. "With a good casing, you can prevent most of our attacks," Kim said.

Axarhöfði 14,

110 Reykjavik, Iceland