Software in a song can be used to control vehicles

The modern car's operating system is such a mess that researchers were once able to get complete control of a vehicle by playing a song laced with malicious code.

Malware encoded in the track was executed after the file was loaded from a CD and processed by a buggy parser. "A car is a big distributed system with wheels connected, and that's been true for 20 years," said Stefan Savage, professor of computer science at the University of California, San Diego.

Malware encoded in the track was executed after the file was loaded from a CD and processed by a buggy parser. "A car is a big distributed system with wheels connected, and that's been true for 20 years," said Stefan Savage, professor of computer science at the University of California, San Diego.

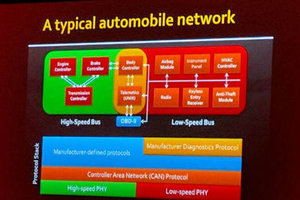

"It's one of the most complex distributed systems you own, with 35-40 electronic control units and dozens of operating systems working together." Speaking at the Usenix Enigma conference in San Francisco on Tuesday, Savage detailed six years of research into automotive systems. You read some of that research here [PDF] and here [PDF]. Today's cars are a mess of different third-party and OEM software that is poorly written and badly integrated. Vehicles typically run two main networks: a high-speed one for engine, brakes and transmission systems, and a lower-speed version running secondary functions like entertainment and climate control.

But the two networks have to talk to each other, and there is little to stop one compromised gizmo being used to take over the whole vehicle. As an example, Savage revealed that his team had been able to get full control of a vehicle by encoding computer instructions into a song. If the carefully crafted .WMA track was played from a CD, the attacker could get full control – the smuggled code would exploit weaknesses in the playback software to commandeer operations.

Further commands to remote control the vehicle could then be received via the car's builtin cellular connection. "Basically, give me 18 seconds of playtime and we can insert the attack code," Savage told The Register. We understand the security flaw has since been addressed. The spiked music attacked the car's entertainment system, which wasn't locked down and granted the injected code access to the rest of the vehicle's electronics. It's easy to run traffic around the car's networks because it is often required. For example, many cars include a crash detector on the network that can shut down the engine and unlock the car doors in the event of an accident.

Part of the problem is that late-model cars now have to have a government-mandated OBD-II port (typically under the steering wheel above the pedals) and once you get access to that, the car's network is entirely open to you, Savage said. "For cars the OEM is not the developer, they are the integrator, so there are software supply chain issues," he said. "Source code is frequently not available, so code inspection does not work, since no party in the world has access to all of a car's source code."

When asked why car builders didn't take a leaf out of the IT industry's playbook and just use firewalls and intrusion detection systems, Savage said it wasn't that simple. The car's various IT systems all need to work together and that is a difficult process to lock down and pay for. "A firewall is not going to do it, the architecture is too complex and cost really counts to these guys – saying 'It's only a $5 fix per car' doesn't cut it," he said. "That said, there could be a great tinfoil hat boutique business for hackers who want to pimp their cyber ride with a firewall."

Holding back, for everyone's good

Savage and his team documented their car hacking back in 2010, years before Charlie Miller and Chris Valasek conducted their high-profile shenanigans to the delight of magazine journalists. Savage said his group decided not to publish their results in full detail, and to work with the manufacturers and regulators to privately fix the issues they discovered.

"As an academic it felt weird not publishing my research," he said. "But it's a trade off. Had we published then there would be a pool of cars out there that were easily hackable with a little knowledge." The audit, which went largely unnoticed by the media at the time, had very positive results, though. "GM got the security religion hard," Savage said, adding that the firm now has 100 engineers just working on IT security in cars and has a chief security officer just for its automotive division.

In addition, the Society of Automotive Engineers has a cybersecurity committee and Savage said engineers are now thinking about security right at the start of the design process. On the government side, the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration now has a budget for checking software. While Savage might prefer to work behind the scenes, Miller and Valasek's headline-grabbing disclosures served a useful purpose in spurring the automotive industry into action by making them aware of the costs involved when the disclosures provoke a product recall.

"Fiat Chrysler had to recall 1.4 million cars and that cost about a quarter of a billion dollars," Savage said. "That changes the mindset; the notion that you add a quarter-billion charge to your figures because two guys wanted to give a talk at Black Hat woke everyone up." The answer, the prof said, was that cars had to have automatic wireless software updates to fix problems as they are discovered. Manufacturers like Tesla already make use of this and now consumers should demand it. "Every manufacturer now either has remote update or will shortly announce it," he predicted. "The cost of not having it is just too great."

Axarhöfði 14,

110 Reykjavik, Iceland