How hackers eavesdropped on a US Congressman using only his phone number

A US congressman has learned first-hand just how vulnerable cellphones are to eavesdropping and geographic tracking after hackers were able to record his calls and monitor his movements using nothing more than the public ten-digit phone number associated with the handset he used.

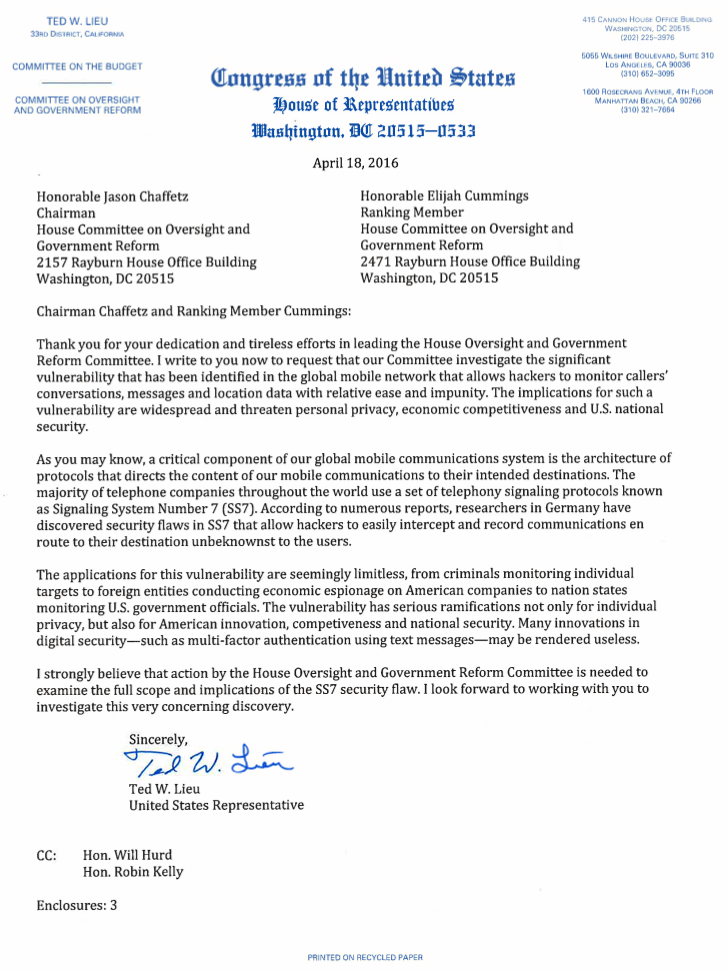

The stalking of US Representative Ted Lieu's smartphone was carried out with his permission for a piece broadcast Sunday night by 60 Minutes.

The stalking of US Representative Ted Lieu's smartphone was carried out with his permission for a piece broadcast Sunday night by 60 Minutes.

Karsten Nohl of Germany-based Security Research Labs was able to record any call made to or from the phone and to track its precise location in real-time as the California congressman traveled to various points in the southern part of the state. At one point, 60 minutes played for Lieu a crystal-clear recording Nohl made of one call that discussed data collection practices by the US National Security Agency. While SR Labs had permission to carry out the surveillance, there's nothing stopping malicious hackers from doing the same thing.

The representative said he had two reactions: "First it's really creepy," he said. "And second it makes me angry. They could hear any call. Pretty much anyone has a cell phone. It could be stock trades you want someone to execute. It could be a call with a bank."

The hack was done by accessing Signalling System No. 7, or SS7, a telephony signalling language used by more than 800 telecommunication companies around the world to allow their networks to interoperate. SS7 is the routing protocol that, for instance, allows a T-Mobile subscriber to connect to the Deutsche Telekom network while traveling in Germany. It also provides a way for someone on one continent to send text messages to a phone located on another continent. SS7 also makes individuals' subscriber data available to anyone with access to SS7.

Weakest link

The problem with SS7 is that it's only as secure as its least secure or trust-worthy member. If any one of the 820 or so telcos that make up the network is hacked or employs a rogue administrator, a wealth of information—including voice calls, text messages, locations, and subscriber data—is open to interception. Some telcos rely on SS7 as a revenue generator by providing legitimate services. For instance, banks may ask a telco to confirm that a US resident's phone is located in Brazil or another overseas location before approving a charge that's made there. The assumption is that if the phone is located in the same place as transaction, there's a good chance the card holder is traveling there and it's safe to approve the transaction.

"As long as you have SS7 access, it's extremely easy," Les Goldsmith, a researcher with Las Vegas security firm ESD, told. "Any one of the telcos that has a roaming agreement with the target network can access the phone." Goldsmith spoke on the topic of SS7 security at last month's RSA conference in San Francisco.

Besides allowing a telco to query the location of phones on other carriers' networks, SS7 allows the telco to route calls and text messages through a proxy before sending it to its final, intended destination. The proxy can spoof its phone number to assume the identity of the person making the call or sending the message. As a result, the person on the receiving end would have no clue the communication is being intercepted or routed through a switch controlled by a third party.

While many carriers say they're in the process of replacing SS7 to more secure protocol known as Diameter, Goldsmith said it will likely remain backward compatible with its predecessor for many years. That means the insecurities of SS7 are likely to remain a threat for the foreseeable future. ESD markets what it says is a solution to SS7 abuse. It comes in the form of a firewall that helps carriers decide which SS7 commands to honor and which ones to ignore. For instance, a query coming from a Russia-based telco seeking the location of a known official with the US Pentagon might be automatically dropped.

According to 60 Minutes, the abuse of SS7 to snoop and eavesdrop on smartphone users is an open secret among the NSA and other intelligence agencies. Lieu sharply criticized any US agencies that may have turned a blind eye to such vulnerabilities. "The people who knew about this flaw should be fired," he said. "You cannot have 300 and some million Americans, and really the global citizenry, be at risk of having their phone conversations intercepted with a known flaw simply because some intelligence agencies might get some data. That is not acceptable."

Axarhöfði 14,

110 Reykjavik, Iceland