Drammer Android hack lets apps take full control of your phone

Earlier last year, security researchers from Google's Project Zero outlined a way to hijack the computers running Linux by abusing a design flaw in the memory and gaining higher kernel privileges on the system.

Now, the same previously found designing weakness has been exploited to gain unfettered "root" access to millions of Android smartphones, allowing potentially anyone to take control of affected devices.

Now, the same previously found designing weakness has been exploited to gain unfettered "root" access to millions of Android smartphones, allowing potentially anyone to take control of affected devices.

Researchers in the VUSec Lab at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam have discovered a vulnerability that targets a device's dynamic random access memory (DRAM) using an attack called Rowhammer. Although we are already aware of the Rowhammer attack, this is the very first time when researchers have successfully used this attack to target mobile devices. What is DRAM Rowhammer Attack? The Rowhammer attack against mobile devices is equally dangerous because it potentially puts all critical data on millions of Android phones at risk, at least until a security patch is available.

The Rowhammer attack involves executing a malicious application that repeatedly accesses the same "row" of transistors on a memory chip in a tiny fraction of a second in a process called "Hammering." As a result, hammering a memory region can disturb neighboring row, causing the row to leak electricity into the next row which eventually causes a bit to flip. And since bits encode data, this small change modifies that data, creating a way to gain control over the device.

In short, Rowhammer is an issue with new generation DRAM chips in which repeatedly accessing a row of memory can cause "bit flipping" in an adjacent row that could allow anyone to change the value of contents stored in the memory.

Is Your Android Phone Vulnerable?

To test the Rowhammer attack on mobile phones, the researchers created a new proof-of-concept exploit, dubbed DRAMMER, and found their exploit successfully altered crucial bits of data in a way that completely roots big brand Android devices from Samsung, OnePlus, LG, Motorola, and possibly other manufacturers. The researchers successfully rooted Android handsets including Google's Nexus 4 and Nexus 5; LG's G4; Samsung Galaxy S4 and Galaxy S5, Motorola's Moto G models from 2013 and 2014; and OnePlus One.

How does the DRAMMER Attack Work? (Exploit Source Code)

The researchers created an app — containing their rooting exploit — that requires no special user permissions in order to avoid raising suspicion. The DRAMMER attack would then need a victim to download the app laced with malware (researchers' exploit code) to execute the hack.

The researchers took advantage of an Android mechanism called the ION memory allocator to gain direct access to the dynamic random access memory (DRAM). Besides giving every app direct access to the DRAM, the ION memory allocator also allows identifying adjacent rows on the DRAM, which is an important factor for generating targeted bit flips.

Knowing this, the researchers then had to figure out how to use the bit flipping to achieve root access on the victim's device, giving them full control of the target phone and the ability to do anything from accessing data to taking photos. "On a high level, our technique works by exhausting available memory chunks of different sizes to drive the physical memory allocator into a state in which it has to start serving memory from regions that we can reliably predict," the paper reads.

"We then force the allocator to place the target security-sensitive data, i.e., a page table, at a position in physical memory which is vulnerable to bit flips and which we can hammer from adjacent parts of memory under our control." Once you download this malicious app, the DRAMMER exploit takes over your phone within minutes – or even seconds – and runs without your interaction. The attack continues to run even if you interact with the app or put your phone in "sleep" mode.

The researchers expect to soon publish an app [source code available here] that will let you test your Android smartphone yourself and anonymously include your results in a running tally, which will help researchers track the list of vulnerable devices.

DRAMMER Has No Quick Fix

The group of researchers privately disclosed its findings to Google in July, and the company designated the flaw as "critical," awarding the researchers $4,000 under its bug bounty program. Google says the company has informed its manufacturing partners of the issue earlier this month and has developed a mitigation which it will include in its upcoming November security bulletin to make the DRAMMER attack much harder to execute.

However, the researchers warned that one could not replace the memory chip in Android smartphones that have already been shipped. And even some software features that DRAMMER exploits are so fundamental and essential to any OS that they are difficult to remove or modify without impacting the user experience. In short, the attack is not easy to patch in the next generation of Android phones.

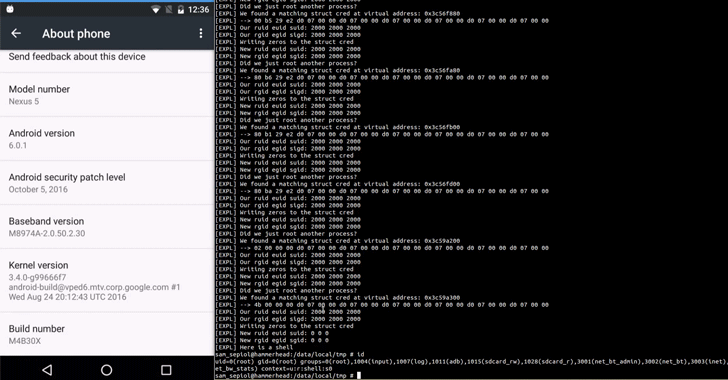

Video Demonstration of DRUMMER Attack on Android 6.0.1

The researchers have also published two proof-of-concept videos that demonstrate DRAMMER attack in action against an unrooted LG Nexus 5. In the first video, the phone is running Android 6.0.1 with security patches Google released on October 5.

In the second video, the researchers show how the DRAMMER attack can be combined with Stagefright bug that remains unpatched in many older Android handsets.

The Stagefright exploit gives the researchers an advanced shell, and by running the DRAMMER exploit, the shell gains root access. The researcher's exploit can target the majority of the world's Android phones.

The group research focuses on Android rather than iOS because the researchers are intimately familiar with the Google's mobile OS which is based on Linux. But the group says it would theoretically be possible to replicate the same attack in an iPhone with additional research.

A team of researchers from VUSec at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, the University of California at Santa Barbara, and the Graz University of Technology has conducted the research, and they'll be presenting their findings later this week at the 23rd ACM Conference on Computer and Communications Security in Vienna, Austria.

Axarhöfði 14,

110 Reykjavik, Iceland