Switcher hacks Wi-Fi routers, switches DNS

One of the most important pieces of advice on cybersecurity is that you should never input logins, passwords, credit card information, and so forth, if you think the page URL looks weird.

Weird links are sometimes a sign of danger. If you see, say, fasebook.com instead of facebook.com, that link is weird. But what if the fake Web page is hosted on the legitimate page? It turns out this scenario is actually plausible — and the bad guys don’t even need to hack the server that hosts the target page.

Weird links are sometimes a sign of danger. If you see, say, fasebook.com instead of facebook.com, that link is weird. But what if the fake Web page is hosted on the legitimate page? It turns out this scenario is actually plausible — and the bad guys don’t even need to hack the server that hosts the target page.

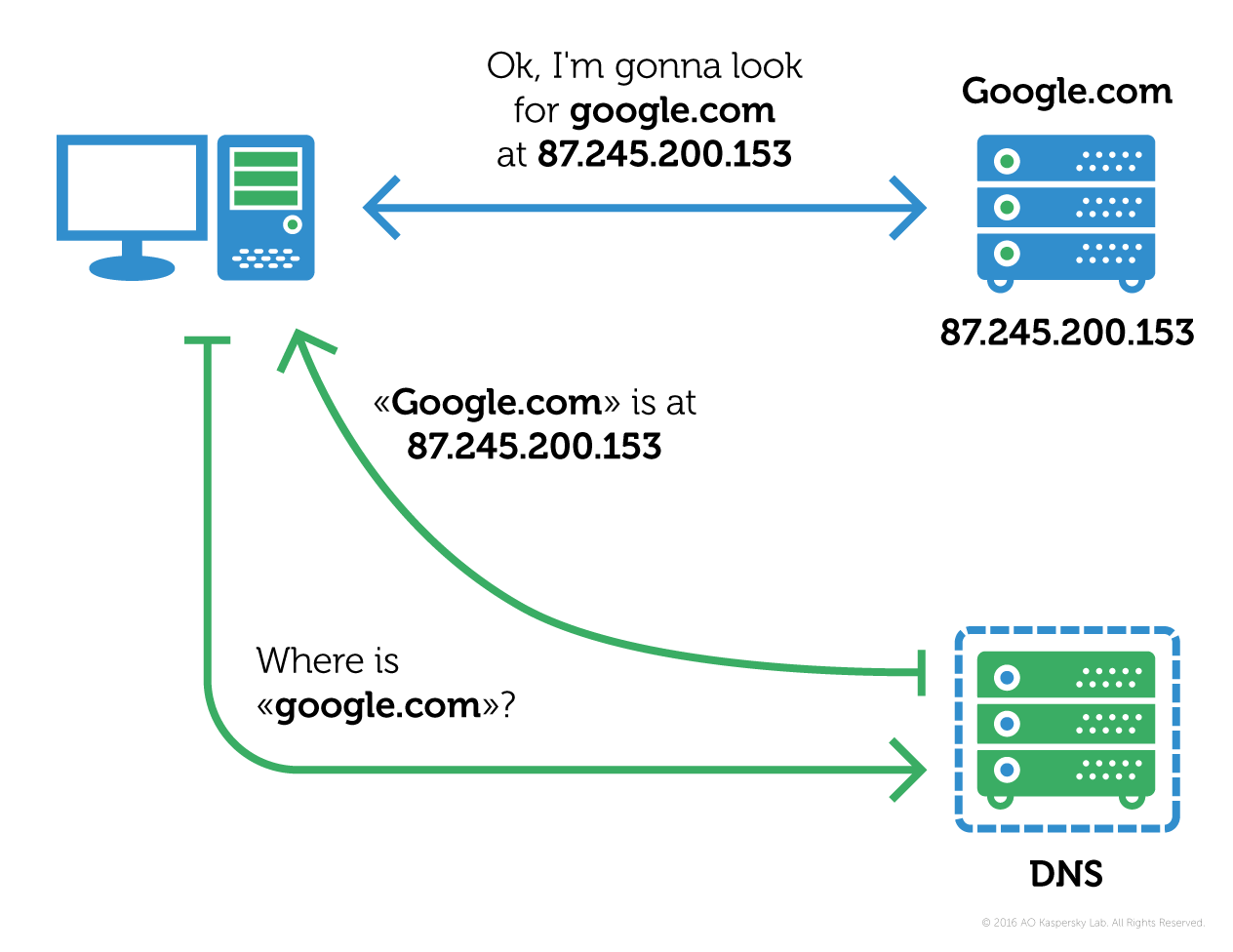

Let’s examine how it works. The trick here is in the way our normal-looking Web page addresses are an add-on to real the IP addresses the Internet works with. This add-on is called DNS — the Domain Name System. Every time you enter a website address in the browser’s address bar, your computer sends a request to a designated DNS server, which returns the address of the domain you need.

For example, when you enter google.com, the respective DNS server returns the IP address 87.245.200.153 — that is where you are effectively being directed. This is how it happens, in a nutshell:

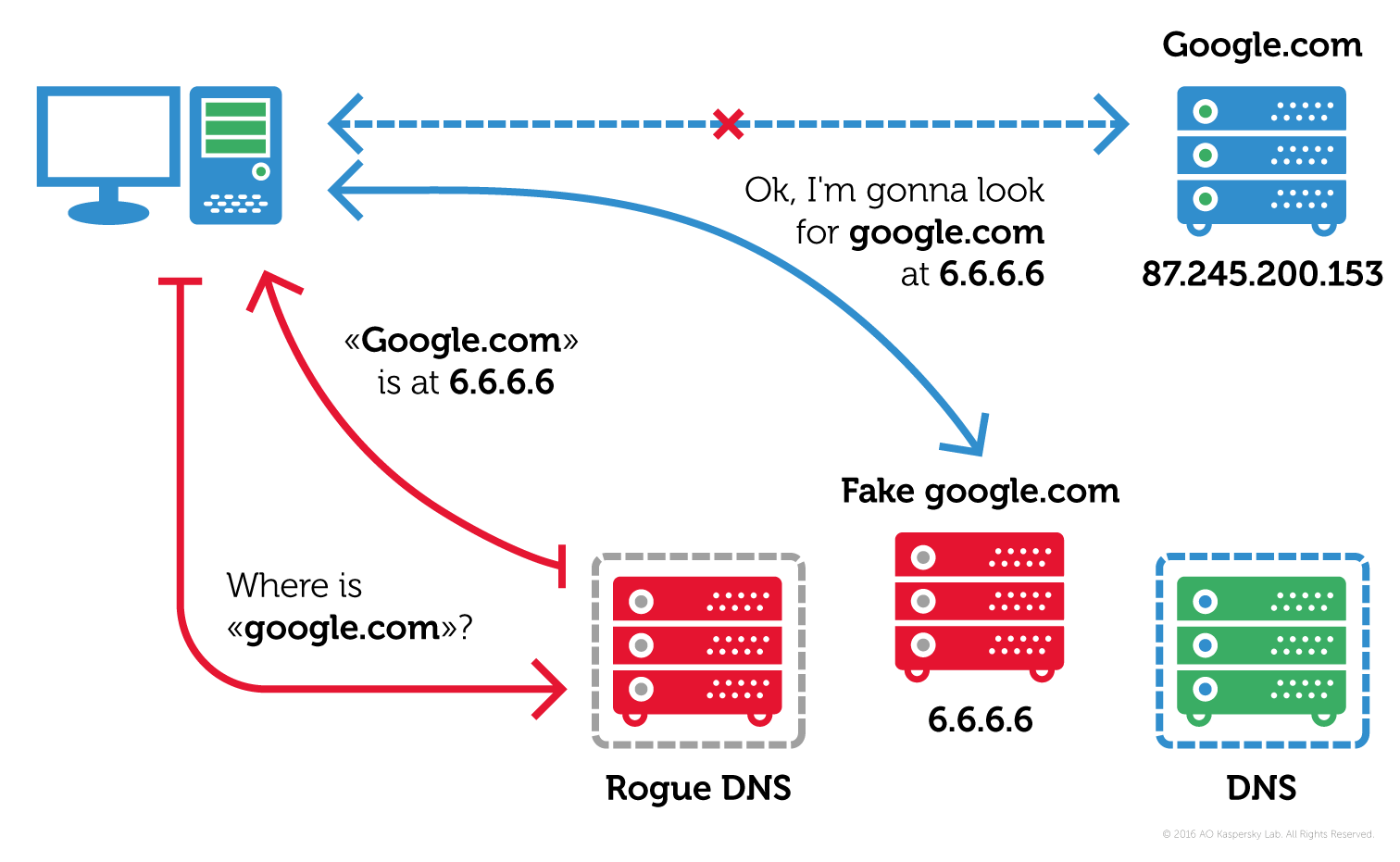

The thing is, malefactors can create their own DNS server that returns another IP address (say, 6.6.6.6) in response to your “google.com” request, and that address might host a malicious website. This method is called DNS hijacking.

Now, the success of the venture depends on having a method that makes a victim use a malicious DNS server, which will direct them to a fake website, instead of a legitimate one. Here is how the creators of the Switcher Trojan solved this problem.

How Switcher works

The Switcher developers created a couple of Android apps, one of which mimics Baidu (a Chinese Web search app, analogous to Google), and another that poses as a public Wi-Fi password search app, which helps users to share passwords to public hotspots; this type of service is also quite popular in China.

Once the malicious app infiltrates the target smartphone connected to a Wi-Fi network, it communicates to a command-and-control (C&C) server and reports that the Trojan has been activated in a particular network. It also provides a network ID.

Then Switcher starts hacking the Wi-Fi router. It tests various admin credentials to log in to the settings interface. Judging by the way this part of the Trojan works, right now the method is functional only if TP-Link routers are used.

If the Trojan manages to identify the right credentials, it goes to the router’s settings page and changes the legitimate default DNS server address to a malicious one. Also, the malware sets a legitimate Google DNS server at 8.8.8.8 as the secondary DNS, so that the victim doesn’t notice anything if the malicious DNS server is down.

On the majority of wireless networks, devices get their network settings (including the address of a DNS server) from routers, so all users who get connected to a compromised network will use the malicious DNS server by default.

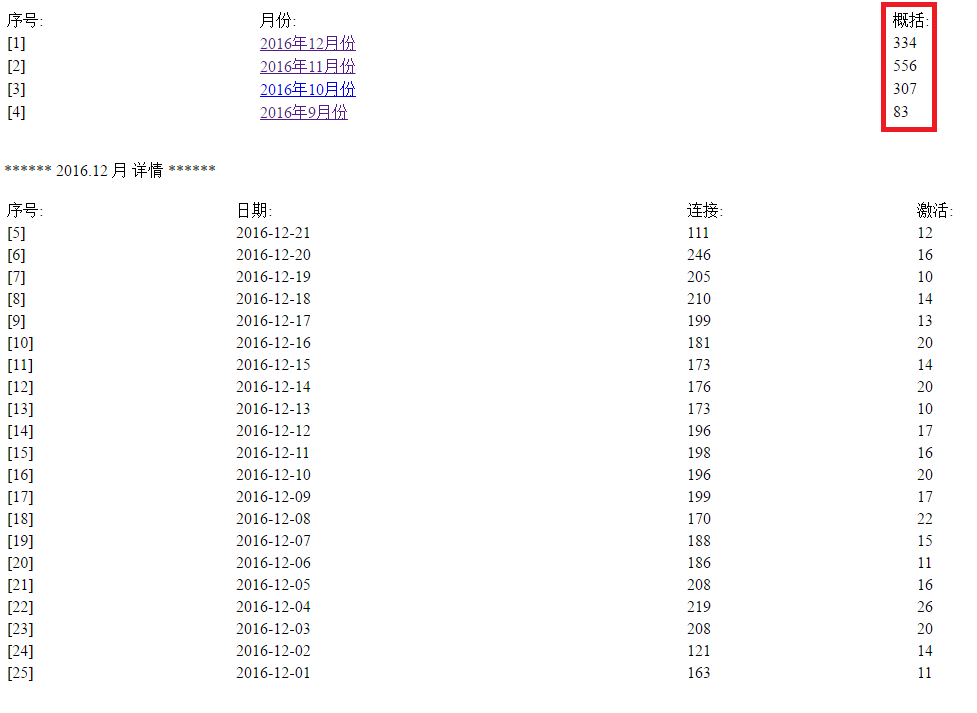

The Trojan reports its successes to the C&C server. Our experts, who found it, were lucky to discover stats of successful attacks, carelessly left lying around in the public part of the website.

If Switcher’s numbers are accurate, in less than four months, the malware has managed to infect 1,280 wireless networks, with all user traffic from those hotspots at the disposal of the culprits.

How to protect against these attacks

1. Apply the right settings to the router. First of all, change the default password to a more sophisticated one.

2. Don’t install suspicious apps on your Android smartphone. Stick with the official app store — although unfortunately, at times Trojans find their way to them, official app stores are still far more reliable than unofficial ones.

3. Use a robust antivirus on all of your devices for maximum protection.

Axarhöfði 14,

110 Reykjavik, Iceland