Hackers say they've broken face ID a week after iPhone X release

When Apple released the iPhone X on November 3, it touched off an immediate race among hackers around the world to be the first to fool the company's futuristic new form of authentication.

A week later, hackers on the actual other side of the world claim to have successfully duplicated someone's face to unlock his iPhone X—with what looks like a simpler technique than some security researchers believed possible.

A week later, hackers on the actual other side of the world claim to have successfully duplicated someone's face to unlock his iPhone X—with what looks like a simpler technique than some security researchers believed possible.

On Friday, Vietnamese security firm Bkav released a blog post and video showing that—by all appearances—they'd cracked Face ID with a composite mask of 3-D-printed plastic, silicone, makeup, and simple paper cutouts, which in combination tricked an iPhone X into unlocking. That demonstration, which has yet to be confirmed publicly by other security researchers, could poke a hole in the expensive security of the iPhone X, particularly given that the researchers say their mask cost just $150 to make. But it's also a hacking proof-of-concept that, for now, shouldn't alarm the average iPhone owner, given the time, effort, and access to someone's face required to recreate it.

Bkav, meanwhile, didn't mince words in its blog post and FAQ on the research. "Apple has done this not so well," writes the company. "Face ID can be fooled by mask, which means it is not an effective security measure."

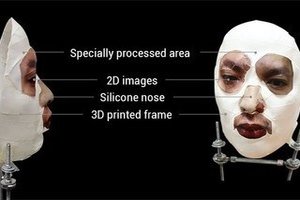

In the video posted to YouTube, shown above, one of the company's staff pulls a piece of cloth from a mounted mask facing an iPhone X on a stand, and the phone instantly unlocks. Despite the phone's sophisticated 3-D infrared mapping of its owner's face and AI-driven modeling, the researchers say they were able to achieve that spoofing with a relatively basic mask: little more than a sculpted silicone nose, some two-dimensional eyes and lips printed on paper, all mounted on a 3-D-printed plastic frame made from a digital scan of the would-be victim's face.

The researchers concede, however, that their technique would require a detailed measurement or digital scan of a the face of the target iPhone's owner. That puts their spoofing method in the realm of highly targeted espionage, rather than the sort of run-of-the-mill hacking most iPhone X owners might face.

"Potential targets shall not be regular users, but billionaires, leaders of major corporations, nation leaders, and agents like FBI need to understand the Face ID's issue," the Bkav researchers write. They also suggest that future versions of their technique might be performed with a quick smartphone scan of a victim’s face, or even a model created from photographs, but didn't make any predictions about how easy those next steps might be to engineer.

Aside from the challenge of acquiring an accurate face scan, the researchers’ simpler setup outperformed more expensive techniques for attempted Face ID trickery—namely, the ones we tried earlier this month. With the help of a special effects artist, and at a cost of thousands of dollars, we created full masks cast from a staffer's face in five different materials, ranging from silicone to gelatin to vinyl. Despite details like eyeholes designed to allow real eye movement, and thousands of eyebrow hairs inserted into the mask intended to look more like real hair to the iPhone's infrared sensor, none of our masks worked.

By contrast, the Bkav researchers say they were able to crack Face ID with a cheap mix of materials, 3-D printing rather than face-casting, and perhaps most surprisingly, fixed, two-dimensional printed eyes. The researchers haven't yet revealed much about their process, or the testing that led them to that technique, which may prompt some skepticism. But they say that it was based in part on the realization that Face ID's sensors only checked a portion of a face's features, which experts had previously confirmed in our own testing.

"The recognition mechanism is not as strict as you think," the Bkav researchers write. "We just need a half face to create the mask. It was even simpler than we ourselves had thought." Without more details on its process, however, plenty about Bkav's work remain unclear. The company didn't immediately respond to a long list of questions, saying that it plans to reveal more in a press conference later this week.

Most prominent among those questions, points out security researcher Marc Rogers, is how exactly the phone was registered and trained on its owner's real face. Bkav's staff could have potentially "weakened" the phone's digital model by training it on its owner's face while some features were obscured, Rogers suggests, essentially teaching the phone to recognize a face that looked more like their mask, rather than create a mask that truly looks like the owner's face.

"For the moment I can't rule out that these guys might be tricking us a bit," says Rogers, a researcher for security firm Cloudflare, who worked on our initial attempts to crack Face ID, and was also one of the first to break Apple's Touch ID fingerprint reader in 2013.

But Bkav's history lends its demonstration some credence. Nearly a decade ago, the company's researchers found that they could break the facial recognition of laptop makers including Lenovo, Toshiba, and Asus, with nothing more than two-dimensional images of a user's face. They presented those widely cited findings at the 2009 Black Hat security conference.

If Bkav's findings do check out, Rogers says that the most unexpected result of the company's research would be that even fixed, printed eyes are able to deceive Face ID. Apple patents had led Rogers to believe that Face ID looked for eye movement, he says. Without it, Face ID would be left vulnerable not only to simpler mask spoofs, but also attacks that could unlock an iPhone X even if the owner is sleeping, restrained, or potentially even dead.

The last of those situations is especially worrying, since it would theoretically be a problem for Face ID that even Touch ID didn't present, given that the latter checks for the conductivity of a living person's finger before unlocking. "That would mean this could be tricked without any liveness test at all," Rogers says. "I would say if this is all confirmed, it does mean Face ID is less secure than Touch ID." It's also unclear if Face ID uses any methods beyond eye movement to indicate that someone is alive.

Despite the potential threat of snooping on a sleeping, kidnapped, or dead person’s iPhone X, Rogers considers the notion that someone will make a silicone-and-plastic mask of the average person's face far-fetched. A far more practical concern is someone simply tricking a victim into glancing at their phone. "This is still not the kind of attack the average person on the street should worry about," Rogers says of Bkav's work. "It’s still probably easier to snatch the phone and just show it to someone to unlock it."

Axarhöfði 14,

110 Reykjavik, Iceland