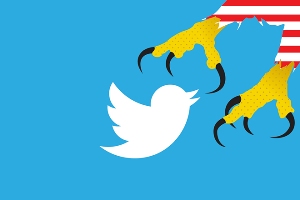

Twitter sues the government of the USA

Twitter just sued the federal government over restrictions the government places on how much the company can disclose about surveillance requests it receives. For months, Twitter has tried to negotiate with the government to expand the kind of information that it and other companies are allowed to disclose. But it failed.

Twitter asserts in its suit that preventing the company from telling users how often the government submits national security requests for user data is a violation of the First Amendment.

Twitter asserts in its suit that preventing the company from telling users how often the government submits national security requests for user data is a violation of the First Amendment.

The move goes a step beyond a challenge filed by Google and other companies last year that also sought permission on First Amendment grounds to disclose how often it receives national security requests for data. In the wake of the Edward Snowden leaks about government spying and the so-called PRISM program, the companies sought to add statistics about national security requests to transparency reports that some of them were already publishing.

Up to that point, the reports had revealed only the number of general law enforcement requests for data that the companies received each year, not so-called National Security Letters the companies received for data or other national security requests submitted with a court order from the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act Court.

The companies asserted that without the ability to disclose more details about the data requests they received, the public was left to speculate wildly that they were providing unfettered access to user data or giving the government information in bulk. If the public knew how few requests for data they actually received, they argued, people would be re-assured that this was not the case.

Although the companies won a partial victory in negotiation when the government agreed earlier this year to let them publish broad statistics about national security requests they received, the statistics turned out to be nothing more than a coy tease. They provided no real transparency. The companies were only allowed to publish a range of the requests they received.

For example, they were only allowed to disclose that they had received between 0 and 999 national security requests for data. They also had a six-month delay imposed on them, prohibiting them from disclosing certain sets of information, and a two-year delay for disclosing other sets of data. In August, Google and Microsoft pressed for the right to release more statistics, including a breakdown of the number of requests specifically targeting user content, versus requests seeking metadata.

Twitter’s Separate Fight

Twitter was not part of the legal challenges filed by the other companies but engaged in its own battle for more transparency. Last April, the company submitted a draft of the kind of transparency report it sought to make public.

Twitter sought, among other things, to narrow the scope for reporting statistics. Instead of reporting requests in a range of 0 to 999, it wanted to be able to report actual aggregate numbers for the number of NSL and FISA orders it received and to be able to break down, in smaller batches, each type of request. For example, it wanted to be able to report the number of NSLs and FISA orders it received in a range of 1-99.

The Justice Department responded in September that the proposed report contained classified information—without specifying which part of the information was classified—that could not be publicly released under the current FISA and National Security Letter laws. These statutes come with a gag order preventing service providers from disclosing the data requests they receive.

“Twitter’s ability to respond to government statements about national security surveillance activities and to discuss the actual surveillance of Twitter users is being unconstitutionally restricted by statutes that prohibit and even criminalize a service provider’s disclosure of the number of national security letters (“NSLs”) and court orders issued pursuant to FISA that it has received, if any.”

Twitter also took issue with the vagueness of the government’s response, which did not specify what part of its proposed transparency report could not be published, preventing Twitter from publishing any of it. “When the government intrudes on speech, the First Amendment requires that it do so in the most limited way possible,” Twitter wrote in its filing. “The government has failed to meet this obligation.”

First Amendment Rights

The American Civil Liberties Union applauded the legal challenge to the gag orders. “If these laws prohibit Twitter from disclosing basic information about government surveillance, then these laws violate the First Amendment,” said Jameel Jaffer, deputy legal director for the ACLU, in a statement. “The Constitution doesn’t permit the government to impose so broad a prohibition on the publication of truthful speech about government conduct.

Twitter’s constitutional challenge is in good company and may have been emboldened by a court decision in another case last year. In that case, a U.S. District Judge ruled that so-called National Security Letters that come with an automatic gag order on the recipient are an unconstitutional impingement on free speech.

That ruling involves a challenge filed by the Electronic Frontier Foundation in 2011 on behalf of an unidentified ISP. The timing of the Twitter suit may not be coincidental. A federal appeals court is scheduled to hear oral arguments in the EFF case in San Francisco tomorrow.

Axarhöfði 14,

110 Reykjavik, Iceland