Anyone can play anything typed into a Google Doc back

If you’ve ever typed anything into a Google Doc, you can now play it back as if it were a movie — like traveling through time to look over your own shoulder as you write.

This is possible because every document written in Google Docs since about May 2010 has a revision history that tracks every change, by every user, with timestamps accurate to the microsecond; these histories are available to anyone with “Edit” permissions; and I have written a piece of software that can find, decode, and rebuild the history for any given document.

This is possible because every document written in Google Docs since about May 2010 has a revision history that tracks every change, by every user, with timestamps accurate to the microsecond; these histories are available to anyone with “Edit” permissions; and I have written a piece of software that can find, decode, and rebuild the history for any given document.

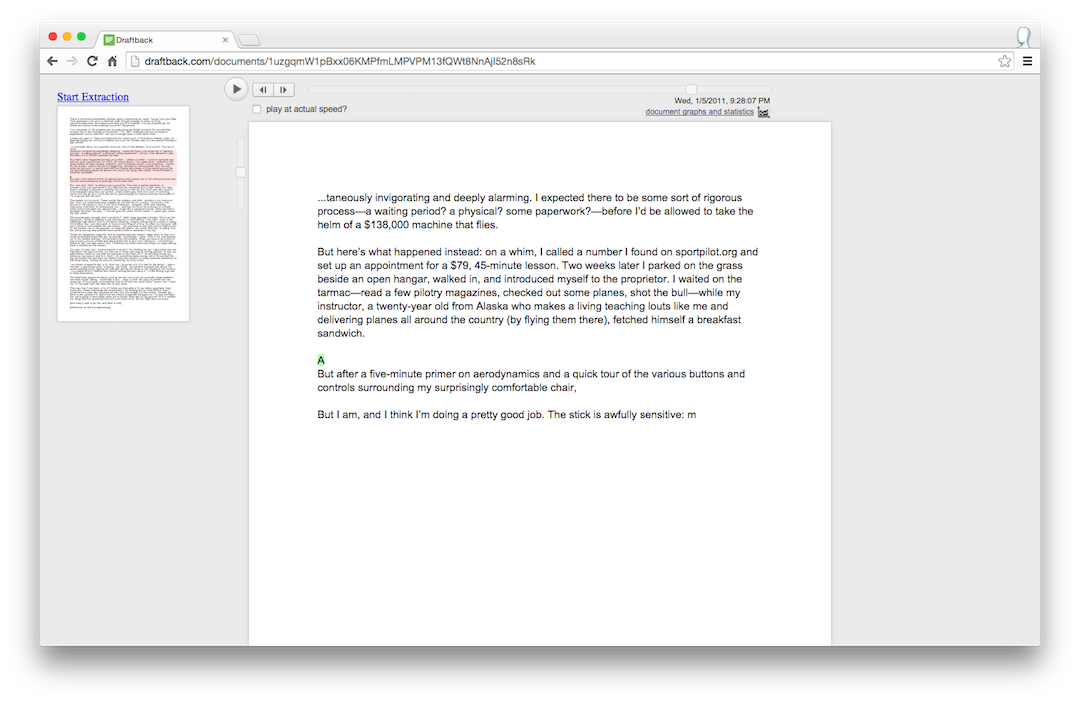

It’s like a video player, but made especially for writing. This one’s from an Atlantic article I began work on nearly four years ago, on the day after Christmas in 2010. The article was about the first (and only) time I got to fly a small airplane. At the time, I didn’t give the slightest thought to the idea that one day I’d be able to watch the draft unfold. But since I happened to write this one in Google Docs, I can recover every keystroke. Above, you can see the first uncertain stirrings of the first paragraph.

What’s neat about this is that I didn’t have to use any special software while I was writing to make this “video” possible. I was working in plain old vanilla Google Docs. And to show you this one paragraph I liked, I didn’t have to present you with the whole document (all 39,154 revisions of it) — I could extract bits and pieces that I thought were interesting, and interleave them in a blog post.

Imagine what a high school English teacher could do with that. Imagine what you could do with that if instead of a minor effort by ol’ Somers here you had, say, a piece by Ta-Nehisi Coates. (I’ve always wanted to watch how TNC writes. If he’s ever used Google Docs, it’s now possible.)

To produce the embed, I used a tool I made called Draftback, which I suppose I’m launching right now. With Draftback, you can play back and analyze any of your own Google Docs, or, for that matter, any Google Doc you have permission to edit.

(Everyone I’ve talked to about this has been surprised, and maybe a little unnerved, to discover that whenever they share a Google Doc with someone, they’re also sharing an extremely detailed record of them typing the thing.)

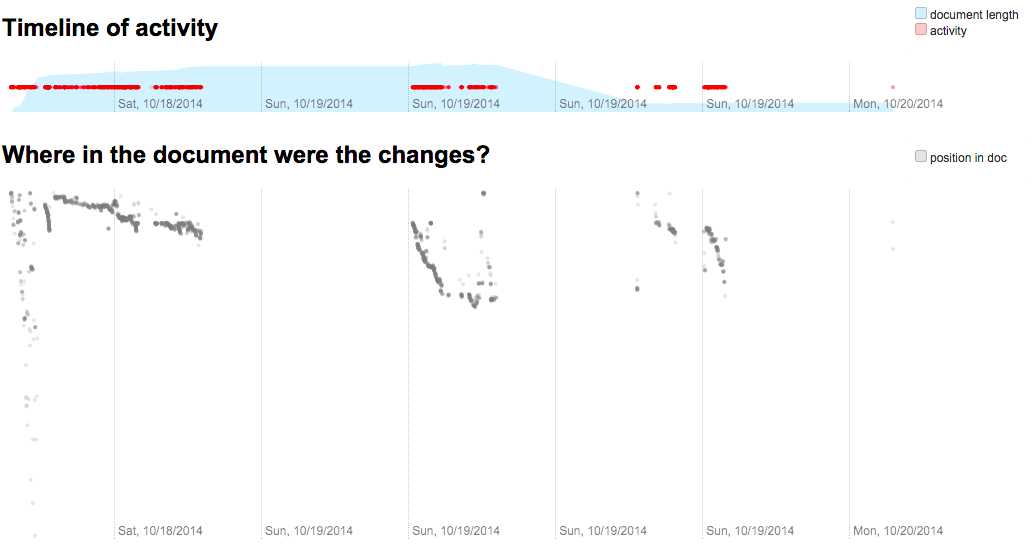

Here’s a graph that Draftback automatically produced for an article I was working on a few weeks ago. It shows the timeline of my changes, and below it, a “map” that tells me where in the document each of those revisions happened: the further down the graph, the further down the page. At the start, I added many thousands of words of notes — that’s why the doc gets so long so fast, and why the edits look sparse. Then you can see that I made three distinct passes, the first one focused on the top of the article, and slow; and the later ones faster and further down. A visual fingerprint of a document, and of a writer.

The data that Google stores is, as you might expect, kind of incredible. What we actually have is not just a coarse “video” of a document — we have the complete history of every single character. Draftback is aware of this history, and assigns each character a persistent unique ID, which makes it possible to do stuff that I don’t think folks have really done to a piece of writing before.

Since Draftback has the full history for every character, and since that history is maintained even as characters are cut and pasted, it’s possible to select some text and see exactly where it came from. It’s like having a four-dimensional view of a document.

Axarhöfði 14,

110 Reykjavik, Iceland