Hacker group robbed 50 banks

In November this year, dignitaries and bigwigs of the cyber security industry gathered inside Europol’s headquarters in The Hague.

As they talked about general issues affecting the community, namely financially-motivated criminals, ears pricked up when one particular strain of malware, called Anunak, was said to have brought about the “armageddon” of the Russian banking industry, according to Andy Chandler, a senior vice president at security firm Fox-IT.

As they talked about general issues affecting the community, namely financially-motivated criminals, ears pricked up when one particular strain of malware, called Anunak, was said to have brought about the “armageddon” of the Russian banking industry, according to Andy Chandler, a senior vice president at security firm Fox-IT.

The Anunak gang has been swiping millions of credit card details from scores of US retailers too, however. It is understood, from a source familiar with investigations into the Anunak malware who spoke on the condition of anonymity, that retailer Staples was also a victim. The stationery giant admitted last week that data on as many as 1.16 million payment cards may have been stolen by the hackers, who infiltrated point-of-sale (PoS) systems at 115 stores. The firm said the malware was siphoning off data between 20 July to 16 September.

Sheplers, a cowboy apparel seller whose PoS systems were infected between June and September, and Bebe, a women’s clothing retailer whose stores were attacked in November, were also victims of the Anunak criminals, according to the source. Security reporter Brian Krebs has previously linked the criminals who breached Staples to those who perpetrated a similar attack on Michaels. They’re not thought to be the same as those who made off with data on tens of millions of credit cards from the USA retail giant Target in 2013 and Home Depot this year. But if the same group is behind all those breaches, it’s doing a startlingly good job of infiltrating PoS systems in the USA, costing the retail industry millions.

The Anunak hackers’ most profitable work, however, has come from attacks on the Russian finance industry. Along with Moscow-based security provider Group-IB, Fox-IT has released a report today detailing the activities of the Anunak hackers, who have snuck into a large number of banks this year and siphoned off as much as $18 million, or one billion roubles. They’ve been able to make off with $2 million per attack, having gained access to networks of more than 50 Russian banks. They’ve even managed to infect 52 separate ATM systems to make off with more cash. In some cases, the damage has been so severe financial institutions have been forced to give up their banking licence.

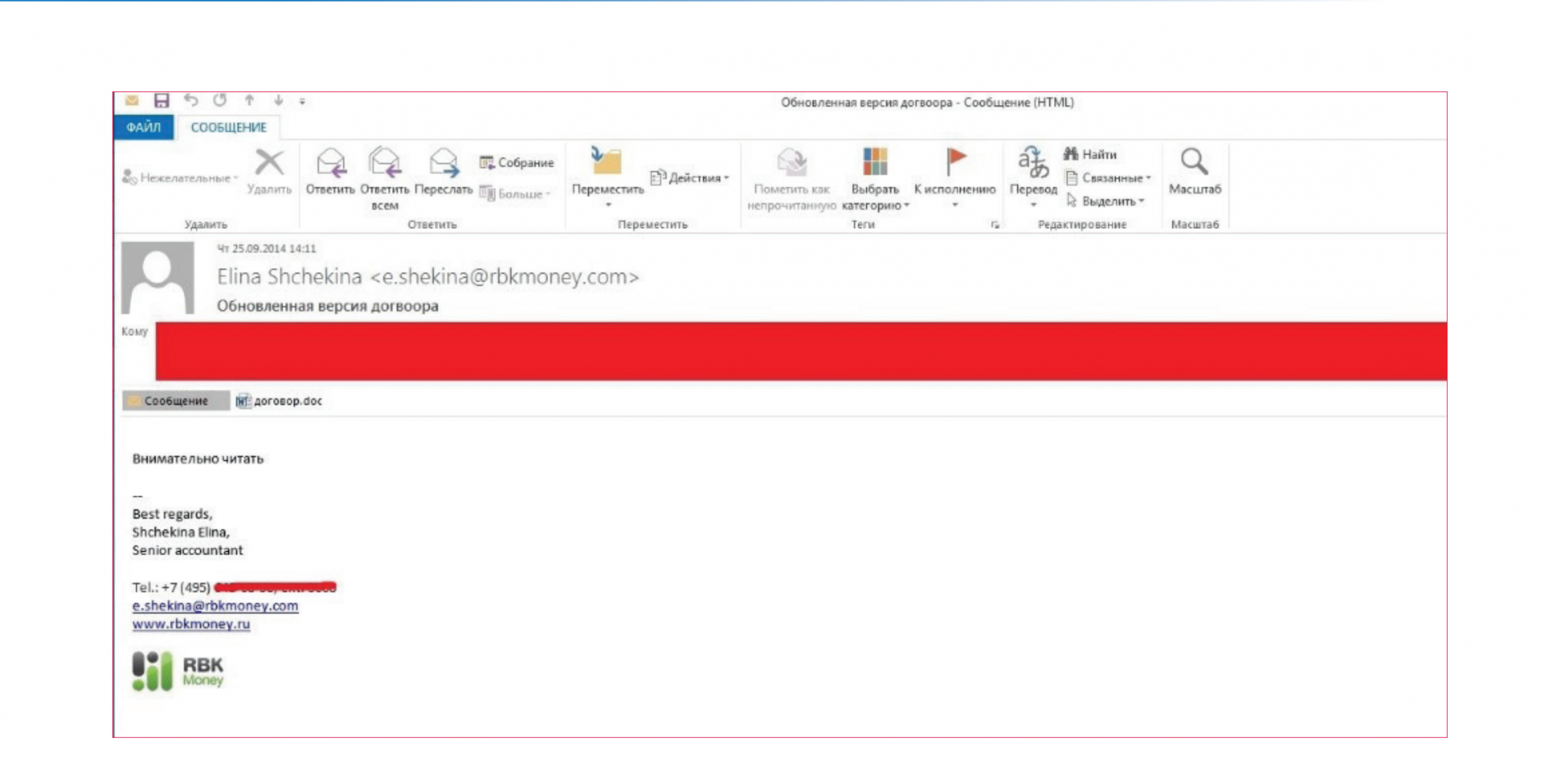

Their modus operandi was typical but effective. It would start with emails to minions of the target organisation, convincing them to open a malicious attachment supposedly delivered by the Central Bank of the Russian Federation. After attacking that single worker’s computer, they hunted for the passwords of someone with administrator control of the network. With those acquired, the Anunak crew took control of email and domain servers, installing their backdoors and other malware along the way. From the email communications, they’d uncover weaknesses within the organisation’s security systems. And for added surveillance, they turned on hacked machines’ video recording capability.

This happened time and again throughout the last two years, though in some cases they partnered with other criminals who already had their malware installed at finance institutions. This included work with the controllers of Zeus, still considered one of the most pernicious bank malware types around.

It was then a case of accessing accounts on the banks’ networks and sending money through various “legal entities”, where money would be held and then passed on, in order to distance the gang from their attacks. They would send funds in chunks of up to $2,000 so as not to alert any fraud detection systems. Otherwise they’d send mules, often immigrants from former Soviet republics, to pick up cash direct from hacked ATMs across different cities.

But the Anunak hackers haven’t limited themselves to US retailers and the finance industries of Russia and the countries of the old Eastern Bloc. They’ve also compromised at least three American media organisations. And where they’ve gained access to government networks, they’ve been doing some apparent espionage too, though the report barely touched on that side of the Anunak crew’s work.

“In our experience the scale of growth and diversity of Russian Banks, US retailers and western businesses with high levels of IP makes this one of the most financially successful cyber gangs we have seen,” added Chandler. The hunt is now on for those behind the Anunak attacks, who have been linked to those responsible for another malware type known as Carberp, says Chandler. Though the leaders of that gang were arrested in 2013, it’s possible a former member is still at large. Whoever is behind Anunak, they’ve quickly become one of the dons of the digital underground.

Axarhöfði 14,

110 Reykjavik, Iceland