What would credit cards of the future be like?

You should know that carders play tricks and your money may easily be stolen. The main reason why it’s still happening is the rudimental card security system, which dates back to the 1970s.

The data on the magnetic strip is written as ‘plain text’, and a PIN, a short security number easily susceptible to theft, serves as the only stronghold of protection for your bank account.

The data on the magnetic strip is written as ‘plain text’, and a PIN, a short security number easily susceptible to theft, serves as the only stronghold of protection for your bank account.

It goes without saying that to deploy more advanced transaction security technologies, the finance industry, which currently loses unbelievable sums of money to all types of scammers, does its best. Now the most successful project of all is the technology of chip-enabled cards (or EMV cards). Following their massive proliferation in Europe and Canada, the number of card cloning cases in these geographies decreased dramatically. Carders who use skimmers seek a better life in USA and Asia where EMV cards are not so widely used.

However advanced the EMV system might be in terms of card protection, it is not ideal and cannot protect against every threat imaginable — provided the skimming techniques also continue to evolve. Of course, there are some tips how to protect your card from fraud. It may well be we’ll be using different types of cards in the foreseeable future. What would they be like? Let’s take a look.

Card on demand

An American company Dynamics provides an even more exotic solution. The card does not have a stable magnetic strip, in the sense of the word. The latter is generated dynamically by the built-in hardware, on demand, and the user first has to enter the password by means of an integrated keyboard.

If you happen to lack a password, the magnetic strip would not be generated and, consequently, the transaction would not be executed. Moreover, such a card does not have an ordinary 16-digit number: a part of the numeric sequence is not printed on the plastic but is displayed on the screen after the cardholder enters the password.

May I have your finger?

Well, passwords are powerful means of protecting your card, but it’s of no use should an absent-minded person fails to keep it secret. We all know stories about ‘wise’ cardholders who would write their PIN on the very card and then lose it.

Biometry-based authentication is a radical solution to this problem. Zwipe, a Norway-based company, in association with Mastercard, is currently running a trial of a credit card with an integrated fingerprint scanner. The only thing you need to approve the transaction is placing your finger on the contact plate and — well, farewell, PIN!

Password and reply

The most obvious solution to the problem is adding another layer of security — like in the two-factor authentication approach used all over the Internet. When paying online, besides a CVV2 security code on the reverse side of the card, a cardholder enters a one-time randomly generated password, either sent to a mobile phone in an SMS, printed by ATM or generated by a bank-authorized hardware appliance, a token. Two-factor authentication may be used even for offline transactions should large sums of money be involved.

Bank cards with an integrated display employ a similar method of authentication. In this case, a regular credit card is equipped with a built-in mini-computer, including an LCD screen and a digital keyboard. Besides generating one-time passwords, it is capable of displaying the balance, the history of transactions, and so on. Although the first interactive cards have been available for over five years, only several banks in Europe, the U.S., and developed Asian countries offer them to customers.

Quantum comes to help

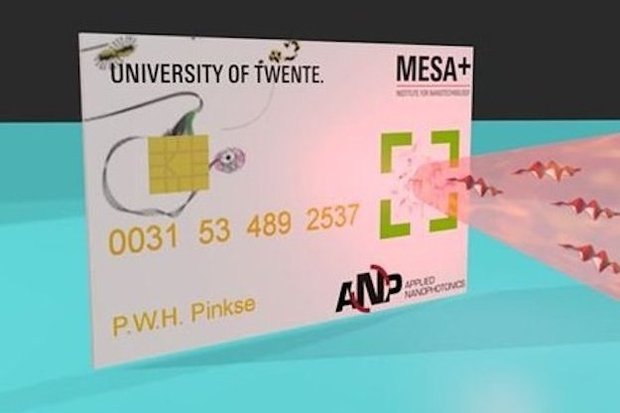

Regardless of decades of research, fully operable quantum computers remain a dream yet to come true. But there is a silver lining: some features of quantum tech will serve to create identifiers that are impossible to spoof. Dutch researches of University of Twente and Eindhoven University of Technology plan to use this concept of a quantum-based security system for credit cards and personal IDs. Although it’s only now available as a lab trial, their model of a quantum-based security system is being developed under the name of secure quantum authentication (QSA).

A tiny section of an ordinary plastic card is covered with a very thin layer of zinc oxide (no magic here — a.k.a ‘zinc white’). Then this section is bombarded by discreet laser-emitted photons. When hitting nano-particles, photons randomly reflect inside of the zinc oxide layer. This process alters the optical properties of a particle layer, forming a unique key.

So, if one beacons such a card with a sequence of laser impulses (i.e. ‘asks the question’), they receive a defined reflection pattern (i.e. ‘the answer’). A combination of unique ‘question-answer’ bundles is stored in the bank data system and is used to authenticate the key.

If a culprit tries to hijack a question and answer combination during the transaction it doesn’t work. Any additional photoelectric detector implanted into the system would destroy the quantum state of at least part of the photons and will corrupt the whole process for the attacker.

An alternative method of hacking this security system presupposes card forgery, keeping exact size, location and other parameters of the nano-particles in order to produce an accurate copy, and is practically unfeasible due to the high complexity of the process. QSA developers claim that, regardless of a seemingly complex concept, this technology is relatively simple and cheap to deploy using readily available tech and methods.

Make haste slowly

It is quite unlikely banks would deploy the above mentioned security systems soon. The finance industry is quite conservative and render it costly to roll out new tech in deployments of scale. With that in mind, we are quite sure the payment method innovation will first be achievable in alternative non-banking services, including, for instance, new payment systems like Apple Pay or Google Wallet, or promising dark horses like Coin, Wocket and Plastc (we’ll share their story a bit later).

Besides, it is crucial all wonders of tech in these sophisticated novelties not be in vain because of imperfections in the deployment process, as it frequently happens with EMV cards. The main security problem in this respect is that in case a terminal is not able to read data from a secure chip, it will turn to the good old magnetic strip, which remained there for the sake of backward compatibility. Then the entire effort is down the drain.

Axarhöfði 14,

110 Reykjavik, Iceland