A secret catalogue of government gear for spying on your cellphone

The intercept has obtained a secret, internal U.S. government catalogue of dozens of cellphone surveillance devices used by the military and by intelligence agencies.

The document, thick with previously undisclosed information, also offers rare insight into the spying capabilities of federal law enforcement and local police inside the United States.

The document, thick with previously undisclosed information, also offers rare insight into the spying capabilities of federal law enforcement and local police inside the United States.

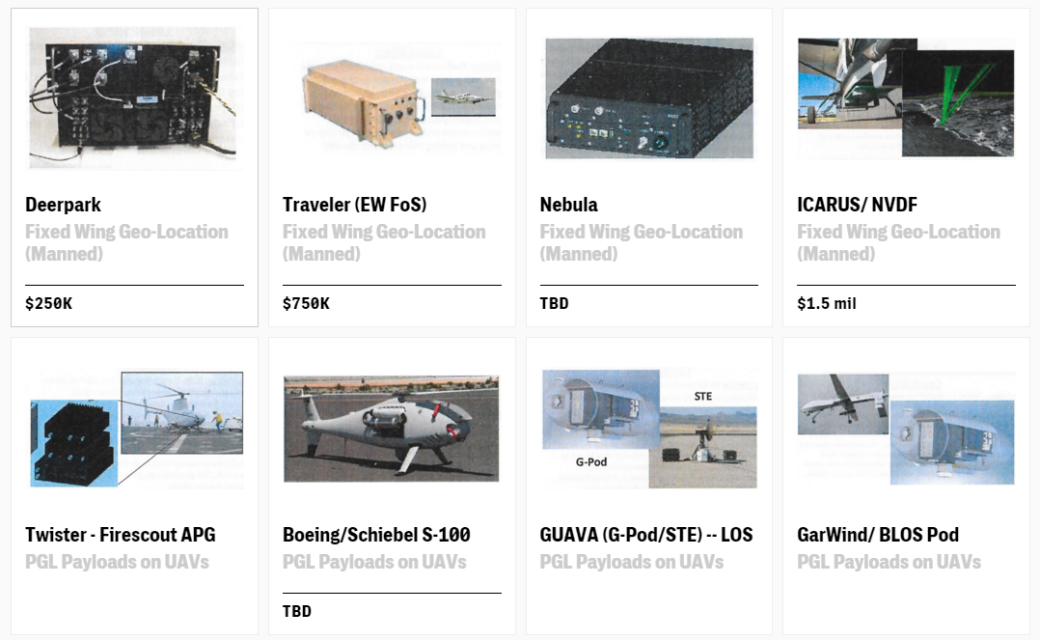

The catalogue includes details on the Stingray, a well-known brand of surveillance gear, as well as Boeing “dirt boxes” and dozens of more obscure devices that can be mounted on vehicles, drones, and piloted aircraft. Some are designed to be used at static locations, while others can be discreetly carried by an individual. They have names like Cyberhawk, Yellowstone, Blackfin, Maximus, Cyclone, and Spartacus. Within the catalogue, the NSA is listed as the vendor of one device, while another was developed for use by the CIA, and another was developed for a special forces requirement. Nearly a third of the entries focus on equipment that seems to have never been described in public before.

The catalogue was obtained from a source within the intelligence community concerned about the militarization of domestic law enforcement. A few of the devices can house a “target list” of as many as 10,000 unique phone identifiers. Most can be used to geolocate people, but the documents indicate that some have more advanced capabilities, like eavesdropping on calls and spying on SMS messages. Two systems, apparently designed for use on captured phones, are touted as having the ability to extract media files, address books, and notes, and one can retrieve deleted text messages.

Above all, the catalogue represents a trove of details on surveillance devices developed for military and intelligence purposes but increasingly used by law enforcement agencies to spy on people and convict them of crimes. The mass shooting earlier this month in San Bernardino, California, which President Barack Obama has called “an act of terrorism,” prompted calls for state and local police forces to beef up their counterterrorism capabilities, a process that has historically involved adapting military technologies to civilian use. Meanwhile, civil liberties advocates and others are increasingly alarmed about how cellphone surveillance devices are used domestically and have called for a more open and informed debate about the trade-off between security and privacy — despite a virtual blackout by the federal government on any information about the specific capabilities of the gear.

“We’ve seen a trend in the years since 9/11 to bring sophisticated surveillance technologies that were originally designed for military use — like Stingrays or drones or biometrics — back home to the United States,” said Jennifer Lynch, a senior staff attorney at the Electronic Frontier Foundation, which has waged a legal battle challenging the use of cellphone surveillance devices domestically. “But using these technologies for domestic law enforcement purposes raises a host of issues that are different from a military context.”

Many of the devices in the catalogue, including the Stingrays and dirt boxes, are cell-site simulators, which operate by mimicking the towers of major telecom companies like Verizon, AT&T, and T-Mobile. When someone’s phone connects to the spoofed network, it transmits a unique identification code and, through the characteristics of its radio signals when they reach the receiver, information about the phone’s location. There are also indications that cell-site simulators may be able to monitor calls and text messages.

In the catalogue, each device is listed with guidelines about how its use must be approved; the answer is usually via the “Ground Force Commander” or under one of two titles in the U.S. code governing military and intelligence operations, including covert action.

But domestically the devices have been used in a way that violates the constitutional rights of citizens, including the Fourth Amendment prohibition on illegal search and seizure, critics like Lynch say. They have regularly been used without warrants, or with warrants that critics call overly broad. Judges and civil liberties groups alike have complained that the devices are used without full disclosure of how they work, even within court proceedings.

“Every time police drive the streets with a Stingray, these dragnet devices can identify and locate dozens or hundreds of innocent bystanders’ phones,” said Nathan Wessler, a staff attorney with the Speech, Privacy, and Technology Project of the American Civil Liberties Union. The controversy around cellphone surveillance illustrates the friction that comes with redeploying military combat gear into civilian life. The U.S. government has been using cell-site simulators for at least 20 years, but their use by local law enforcement is a more recent development.

The archetypical cell-site simulator, the Stingray, was trademarked by Harris Corp. in 2003 and initially used by the military, intelligence agencies, and federal law enforcement. Another company, Digital Receiver Technology, now owned by Boeing, developed dirt boxes — more powerful cell-site simulators — which gained favor among the NSA, CIA, and U.S. military as good tools for hunting down suspected terrorists. The devices can reportedly track more than 200 phones over a wider range than the Stingray.

Amid the war on terror, companies selling cell-site simulators to the federal government thrived. In addition to large corporations like Boeing and Harris, which clocked more than $2.6 billion in federal contracts last year, the catalogue obtained by The Intercept includes products from little-known outfits like Nevada-based Ventis, which appears to have been dissolved, and SR Technologies of Davie, Florida, which has a website that warns: “Due to the sensitive nature of this business, we require that all visitors be registered before accessing further information.” (The catalogue obtained by The Intercept is not dated, but includes information about an event that occurred in 2012.)

The U.S. government eventually used cell-site simulators to target people for assassination in drone strikes, The Intercept has reported. But the CIA helped use the technology at home, too. For more than a decade, the agency worked with the U.S. Marshals Service to deploy planes with dirt boxes attached to track mobile phones across the U.S., the Wall Street Journal revealed.

After being used by federal agencies for years, cellular surveillance devices began to make their way into the arsenals of a small number of local police agencies. By 2007, Harris sought a license from the Federal Communications Commission to widely sell its devices to local law enforcement, and police flooded the FCC with letters of support. “The text of every letter was the same. The only difference was the law enforcement logo at the top,” said Chris Soghoian, the principal technologist at the ACLU, who obtained copies of the letters from the FCC through a Freedom of Information Act request.

The lobbying campaign was a success. Today nearly 60 law enforcement agencies in 23 states are known to possess a Stingray or some form of cell-site simulator, though experts believe that number likely underrepresents the real total. In some jurisdictions, police use cell-site simulators regularly. The Baltimore Police Department, for example, has used Stingrays more than 4,300 times since 2007.

Police often cite the war on terror in acquiring such systems. Michigan State Police claimed their Stingrays would “allow the State to track the physical location of a suspected terrorist,” although the ACLU later found that in 128 uses of the devices last year, none were related to terrorism. In Tacoma, Washington, police claimed Stingrays could prevent attacks using improvised explosive devices — the roadside bombs that plagued soldiers in Iraq. “I am not aware of any case in which a police agency has used a cell-site simulator to find a terrorist,” said Lynch. Instead, “law enforcement agencies have been using cell-site simulators to solve even the most minor domestic crimes.”

The Intercept is not publishing information on devices in the catalogue where the disclosure is not relevant to the debate over the extent of domestic surveillance. The Office of the Director of National Intelligence declined to comment for this article. The FBI, NSA, and U.S. military did not offer any comment after acknowledging The Intercept’s written requests. The Department of Justice “uses technology in a manner that is consistent with the requirements and protections of the Constitution, including the Fourth Amendment, and applicable statutory authorities,” said Marc Raimondi, a Justice Department spokesperson who, for six years prior to working for the DOJ, worked for Harris Corp., the manufacturer of the Stingray.

While interest from local cops helped fuel the spread of cell-site simulators, funding from the federal government also played a role, incentivizing municipalities to buy more of the technology. In the years since 9/11, the U.S. has expanded its funding to provide military hardware to state and local law enforcement agencies via grants awarded by the Department of Homeland Security and the Justice Department. There’s been a similar pattern with Stingray-like devices.

“The same grant programs that paid for local law enforcement agencies across the country to buy armored personnel carriers and drones have paid for Stingrays,” said Soghoian. “Like drones, license plate readers, and biometric scanners, the Stingrays are yet another surveillance technology created by defense contractors for the military, and after years of use in war zones, it eventually trickles down to local and state agencies, paid for with DOJ and DHS money.”

In 2013, the Florida Department of Law Enforcement reported the purchase of two HEATR long-range surveillance devices as well as $3 million worth of Stingray devices since 2008. In California, Alameda County and police departments in Oakland and Fremont are using $180,000 in Homeland Security grant money to buy Harris’ Hailstorm cell-site simulator and the hand-held Thoracic surveillance device, made by Maryland security and intelligence company Keyw. As part of Project Archangel, which is described in government contract documents as a “border radio intercept program,” the Drug Enforcement Administration has contracted with Digital Receiver Technology for over $1 million in DRT surveillance box equipment. The Department of the Interior contracted with Keyw for more than half a million dollars of “reduced signature cellular precision geolocation.”

Information on such purchases, like so much about cell-site simulators, has trickled out through freedom of information requests and public records. The capabilities of the devices are kept under lock and key — a secrecy that hearkens back to their military origins. When state or local police purchase the cell-site simulators, they are routinely required to sign non-disclosure agreements with the FBI that they may not reveal the “existence of and the capabilities provided by” the surveillance devices, or share “any information” about the equipment with the public.

Indeed, while several of the devices in the military catalogue obtained by The Intercept are actively deployed by federal and local law enforcement agencies, according to public records, judges have struggled to obtain details of how they work. Other products in the secret catalogue have never been publicly acknowledged and any use by state, local, and federal agencies inside the U.S. is, therefore, difficult to challenge.

“It can take decades for the public to learn what our police departments are doing, by which point constitutional violations may be widespread,” Wessler said. “By showing what new surveillance capabilities are coming down the pike, these documents will help lawmakers, judges, and the public know what to look out for as police departments seek ever-more powerful electronic surveillance tools.”

Sometimes it’s not even clear how much police are spending on Stingray-like devices because they are bought with proceeds from assets seized under federal civil forfeiture law, in drug busts and other operations. Illinois, Michigan, and Maryland police forces have all used asset forfeiture funds to pay for Stingray-type equipment. “The full extent of the secrecy surrounding cell-site simulators is completely unjustified and unlawful,” said EFF’s Lynch. “No police officer or detective should be allowed to withhold information from a court or criminal defendant about how the officer conducted an investigation.”

Judges have been among the foremost advocates for ending the secrecy around cell-site simulators, including by pushing back on warrant requests. At times, police have attempted to hide their use of Stingrays in criminal cases, prompting at least one judge to throw out evidence obtained by the device. In 2012, a U.S. magistrate judge in Texas rejected an application by the Drug Enforcement Administration to use a cell-site simulator in an operation, saying that the agency had failed to explain “what the government would do with” the data collected from innocent people.

Law enforcement has responded with some limited forms of transparency. In September, the Justice Department issued new guidelines for the use of Stingrays and similar devices, including that federal law enforcement agencies using them must obtain a warrant based on probable cause and must delete any data intercepted from individuals not under investigation. Contained within the guidelines, however, is a clause stipulating vague “exceptional circumstances” under which agents could be exempt from the requirement to get a probable cause warrant.

“Cell-site simulator technology has been instrumental in aiding law enforcement in a broad array of investigations, including kidnappings, fugitive investigations, and complicated narcotics cases,” said Deputy Attorney General Sally Quillian Yates. Meanwhile, parallel guidelines issued by the Department of Homeland Security in October do not require warrants for operations on the U.S. border, nor do the warrant requirements apply to state and local officials who purchased their Stingrays through grants from the federal government, such as those in Wisconsin, Maryland, and Florida.

The ACLU, EFF, and several prominent members of Congress have said the federal government’s exceptions are too broad and leave the door open for abuses. “Because cell-site simulators can collect so much information from innocent people, a simple warrant for their use is not enough,” said Lynch, the EFF attorney. “Police officers should be required to limit their use of the device to a short and defined period of time. Officers also need to be clear in the probable cause affidavit supporting the warrant about the device’s capabilities.”

In November, a federal judge in Illinois published a legal memorandum about the government’s application to use a cell-tower spoofing technology in a drug-trafficking investigation. In his memo, Judge Iain Johnston sharply criticized the secrecy surrounding Stingrays and other surveillance devices, suggesting that it made weighing the constitutional implications of their use extremely difficult. “A cell-site simulator is simply too powerful of a device to be used and the information captured by it too vast to allow its use without specific authorization from a fully informed court,” he wrote.

He added that Harris Corp. “is extremely protective about information regarding its device. In fact, Harris is so protective that it has been widely reported that prosecutors are negotiating plea deals far below what they could obtain so as to not disclose cell-site simulator information. … So where is one, including a federal judge, able to learn about cell-site simulators? A judge can ask a requesting Assistant United States Attorney or a federal agent, but they are tight-lipped about the device, too.”

The ACLU and EFF believe that the public has a right to review the types of devices being used to encourage an informed debate on the potentially far-reaching implications of the technology. The catalogue obtained by The Intercept, said Wessler, “fills an important gap in our knowledge, but it is incumbent on law enforcement agencies to proactively disclose information about what surveillance equipment they use and what steps they take to protect Fourth Amendment privacy rights.”

Axarhöfði 14,

110 Reykjavik, Iceland